8 Lessons for Building the City of the Future

This post is an excerpt from a speech delivered by CallisonRTKL senior vice president Greg Yager at Expo Real 2015 in Munich, Germany in early October.

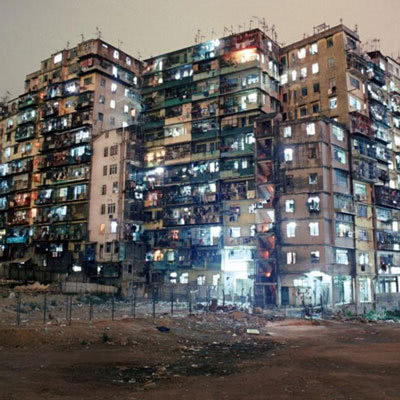

Two decades ago, Kowloon Walled City was demolished. What began as a Chinese military fort in the mid-1800s saw its population soar after the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in World War II. At the height of its existence, nearly 40,000 residents squeezed into 350 buildings, each 12 to 14 stories high, packed into a single city block in New Kowloon, Hong Kong—the densest place on earth. The recent release of “City of Darkness Revisited,” a compilation of photographs, essays and interviews by Greg Girard and Ian Lambot, has reignited interest in the community and its storied past.

PLANNING ON A HUMAN SCALE

Why the continued fascination? It was a city unplanned, unregulated—created largely by its own residents. Architect Aaron Tan, the director of Hong Kong-based firm Research Architecture Design, wrote his graduate thesis on Kowloon Walled City two decades ago and emerged from the process with an unexpected revelation: “We started to see the people could be more intelligent than us, the designers.”

Certainly, architects and designers have an endless supply of tools at our disposal. It’s gotten easier since the days of Kowloon Walled City to densify our cities and make them “smarter.” Technological advances have shown us new and exciting ways to make our trains faster and our buildings taller. It is tempting to get caught up in the race to innovate, but the fundamentals of design teach us to never forget our end user.

From climate change to globalization, crumbling infrastructure to massive population shifts, our world today faces no shortage of pressing, intractable challenges. And nowhere is that urgency more keenly felt than in our cities, which are growing and densifying at an alarming rate across our planet. It is predicted that 70% of an estimated global population of 9 billion will be urban by 2050. But for all the brain power poured into such issues as mass transit, big data, technology or safety, one constant remains: the human being.

From climate change to globalization, crumbling infrastructure to massive population shifts, our world today faces no shortage of pressing, intractable challenges. And nowhere is that urgency more keenly felt than in our cities, which are growing and densifying at an alarming rate across our planet. It is predicted that 70% of an estimated global population of 9 billion will be urban by 2050. But for all the brain power poured into such issues as mass transit, big data, technology or safety, one constant remains: the human being.

LESSONS LEARNED

We know that putting humans first in the planning and design of today’s cities brings measurable benefits in the form of resiliency, economic vitality and heightened quality of life. An honest analysis of what really works uncovers several lessons for today’s planning and urban designers to internalize.

Lesson 1: Respecting and Responding to Context and Climate

With over half of the world’s population living within 60 kilometers of the sea and more and more development popping up along coastlines, nothing is more vital to long-term value and resiliency than planning for the impacts of climate change and sea level rise. As cities around the world—like Sydney, Australia and New York City, for example—consider the future of their waterfronts, the potential to turn these locations into innovation hubs for environmental resiliency is huge. These incubators of urban revolution can play host to a micro-scale approach with global implications.

Lesson 2: Considering Land Use and Mixed-Use

The evolution from mono-use to mixed-use development has unfolded as people increasingly desire a more compact lifestyle: the convenience of living, working and shopping in close proximity. Success is hugely dependent on creating a variety of experiences that accommodate live, work and play functions. In practice, this amounts to combining convenient amenities with a hospitable workplace and a vibrant retail, entertainment and cultural district in a manner that maximizes value.

Lesson 3: Providing Access to Quality Transit

Addressing the unique needs of a project requires designers to understand the urban context, balance market and development goals and take into account multidimensional traffic and transit solutions, including metro, taxis, buses, cars and bicycles.

Lesson 4: Providing High Quality Education

“It takes a village to raise a child.” This old adage may have resonated more with small, rural communities, but creating a tight-knit relationship between educational institutions and the city at large can be immensely advantageous. Investment in education equates to an investment in the future economy. Schools integrated into the community and physically sharing space can benefit from valuable partnerships with companies and organizations who can provide vocational training or volunteer opportunities and, in turn, benefit from fresh ideas and a new pool of talent.

Lesson 5: Providing State-of-the-Art Community and Cultural Facilities

This strategy is directly related to economic vitality and resiliency. Through both human capital and physical density, community and cultural facilities as part of the urban fabric help to multiply the benefits of a mixed-use environment. Not only is the creative industry encouraged, but deliberate connections and partnerships between sectors bolsters the economy, and the city at large attracts an increased amount of talent and number of visitors.

Lesson 6: Diversifying Housing Stock

Government regulations and laws can make it difficult to employ diverse housing stock in a city masterplan. Often, regulations trail behind demographic shifts in the population, creating a disparity between housing needs and available stock. In response, designers are creating new housing types and asking to bend the rules to accommodate demand.

Lesson 7: Providing Public Green Space

Green space is all the more important and desirable in avoiding the “concrete jungle” effect for high-density districts. Other than the obvious environmental benefits, green space can provide a healthy dose of biophilia, leading to greater productivity, higher tenant retention rates, and additional revenue-generating opportunities.

Lesson 8: Investing in the Public Realm

Atmosphere: that elusive quality of a space capable of transcending design and, instead, is shaped by the people and activities that inhabit it. Investing in the public realm is essential to creating memorable places where people wish to return time and time again. It is here that the core identity of the city of the future is shaped—where goodwill and social investment is fostered, and community ties are strengthened. It is here that placemaking becomes essential.

Each of these lessons challenges us to merge our fundamental understanding of the human being and his needs with the high-performance, high-density developments of our time. They recall the philosophy of Charles and Ray Eames’s groundbreaking film Powers of Ten, in which the system of exponential powers is used to visualize the importance of scale, from the infinite expanse of our universe to a tiny atom. In designing the city of the future, we must employ the Powers of Ten to simultaneously think big and think small, and, as the Eameses intended, recognize that “Eventually everything connects—people, ideas, objects. The quality of the connections is the key to quality, per se.”