A Plan for Burning Man

CallisonRTKL’s Phil Walker applies urban design principles to annual counter-culture festival

Pop-up cities, displaced communities and emergency settlements have emerged as a significant challenge for governments and cities around the world. But this struggle isn’t only confined to emergency situations. Burning Man, the legendary annual counter-cultural festival in the Nevada desert, has been grappling with many of these same issues of temporary settlements like sanitation, safety, circulation, communication, transportation and the sudden influx of a population.

Burning Man is truly remarkable. It began in 1986 as a small gathering of 20 people on Baker Beach in San Francisico, burning an 8-FT “Man” sculpture on the Summer Solstice. Over time both the “Man” and the gathering have grown incredibly, relocating to the Black Rock Desert in Nevada and now supporting a festival population of 70,000. The scale and scope of the festival have likewise expanded, encompassing a huge program of art, performance, and countless theme camps, all culminating with the burn of massive 10-story high “Man” structures.

From a design perspective, it presents urban planners with a unique test: once you strip down an urban plan to the very basics, taking away cars, utilities and even money, how do people interact with the urban environment? When a city’s population goes from zero to 70,000 overnight, how do you plan for that kind of incredibly rapid urbanization?

When I saw the competition to create a new urban plan for Burning Man, I was intrigued. I had some notional awareness of the event, but I really had no idea of the scale of it. The aerial images of Black Rock City reveal the scope of the festival. This is truly a desert metropolis that unfolds each year.

Burning Man is a radical community experiment created by and for some of the most creative people around, and any new plan for it would have to strike a balance between the freedom that allows art to flourish with the need for pragmatic considerations for navigation, accessibility and public safety.

The current plan for the festival was developed by Rod Garrett, and it has really done a fine job of fulfilling these community logistical requirements while providing a platform for individual and group expression to occur. There is value in having a familiar framework that is easily understood and that people can return to. That community knowledge in turn benefits new-comers; having people who know already their way around the camp is a real asset in a large settlement.

Although there is great value in maintaining the current framework, there is also the opportunity to use the community plan itself as an expression of the principles of Burning Man, and many of the proposals in the Big Book of Ideas generated from the competition do just that. Burning Man faces many of the same issues that a permanent city does, but because of its temporary nature, it provides an opportunity and freedom for experimentation, expression and learning on an urban scale, and these are the core ideals which are at the heart of the event.

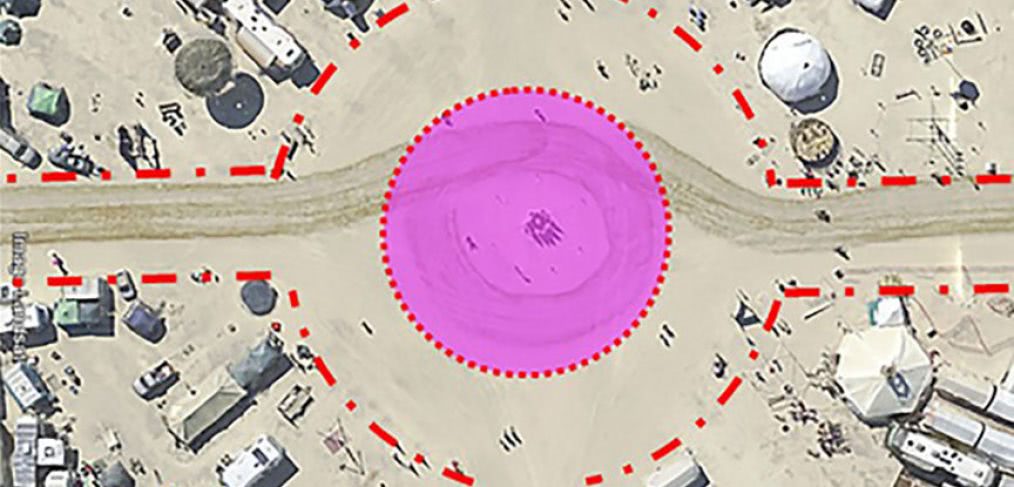

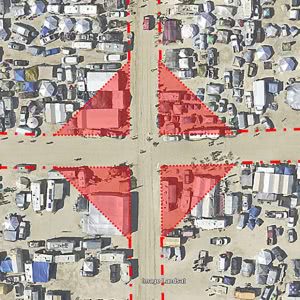

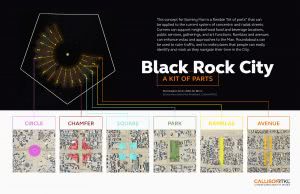

Rather than a wholesale replacement of the existing framework, my approach to the challenge was to suggest providing a flexible “kit of parts” of intersection and street setbacks that can be applied to the current system of concentric and radial streets. The key to these new features is their simplicity; these are simple setbacks that are both easy to lay out and understand, and that have been used in countless urban settlements: the circle, the square, chamfered corners, etc. The toolbox could be expanded and refined and tinkered with from year to year; it would allow for urban experimentation. In many ways, these are the next evolution of urban realm, moving from streets to setbacks from streets.

Although simple, these new spaces have the potential to support a rich layer of public realm in Black Rock City. Expanded corner parks can support neighborhood food and beverage bartering locations, public services, and performance and art functions. Ramblas and avenues can enhance vistas and approaches to the Man. Roundabouts can be used as landmarks for attendees as they navigate during their time in the city. This “neighborhood improvement” approach builds on what is already working at Burning Man by giving it room for more definition and expression.

I don’t see my proposal for Burning Man as a single-use solution but as part of an ongoing dialogue about how we as designers and planners can shape and improve our settlements and gatherings. Burning Man is a great laboratory— a place where ideas can be shared and tested. This is not about commodification or commercialization, but rather about using our skills as designers to solve real problems in our various cities around the world.

Burning Man is a one-week microcosm which showcases many of the fundamental challenges facing urban settlements, both temporary and permanent. It’s also a rare opportunity to see and test urban design principles in action and on a large scale. Burning Man can become an open source laboratory for urban design.