Can You Spark an Urban Renaissance?

Designing for flexibility and human connections in dense urban environments

Sometimes cities just “pop.” It’s typically caused by events beyond our control, like New York’s surge after World War II when other capital cities were destroyed, or an economic phenomenon like the flood of tech companies in Silicon Valley. But thoughtful design, architecture and planning can accelerate these “pops” and even create an urban renaissance. Perhaps more importantly, design can sustain this momentum so it isn’t just a flash in the pan.

The best way to design for this kind of long-term, sustainable growth is through flexibility and prioritizing the connections between people. This has been proven to me again and again, but most recently when I was in Shenzhen working on the design for China Life’s corporate headquarters tower. During my very first trip to the project site, I was interested in visiting a project by another architect.

Looking at the map, I thought it would take me about 15 minutes to walk there. Instead, it took three times as long because much of the urban fabric was rigid and disconnected. I couldn’t cross the street where I needed to, I was forced to walk around entire blocks of buildings and, inevitably, it not only cost me time, but it significantly hindered my ability to enjoy my surroundings.

It’s easy to see how shortsighted urban planning can ruin your commute or make it difficult to get around your city. The opposite is true too—connected planning and flexible architecture can create places where creativity, innovation and community thrive.

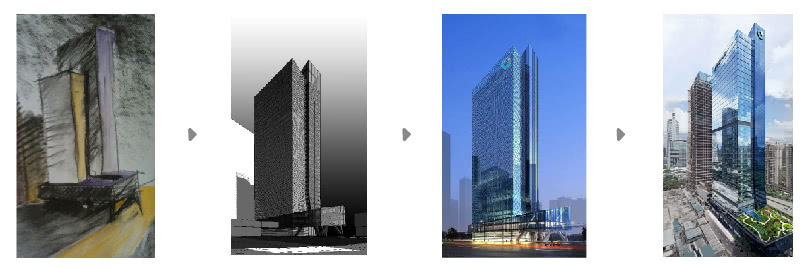

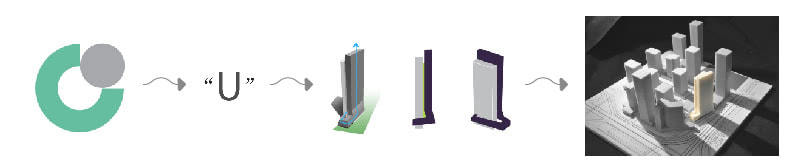

Before and after diagram shows the columns resembeling “roots”

The Flexibility Challenge

In many cities around the world, the built environment is more about building walls and creating boundaries rather than creating a porous urban fabric that allows connectivity. It may seem at first glance that this approach only stops the free flow of people, but it also limits the ability of the city to evolve and stops human interactions; it destroys the potential for organic change and drains life and energy from the city.

Flexibility can alleviate all of these issues, but designing flexibility into a project sounds easier than it is. Technology changes continually, which means that telecommunications infrastructure has to be updated frequently. The International Building Code changes every three years, and interiors workplace spaces typically change with the commercial lease cycle on a 7-10-year basis. The buildings themselves are the most permanent part of the process, standing 30-50 years before they have to be updated or torn down to make way for a new structure.

The asynchronous nature of the renewal process of our social networks, technological infrastructure and built environment creates a challenge to human connection. Most of our existing cities and buildings are not flexible enough to enable ongoing improvements to building and urban performance. Existing laws, codes and business models do not fully support fluid regeneration of the built environment either, and if the built environment doesn’t support creative thought, then it’s not serving our clients. By designing flexible, interconnected environments and infrastructure, we can help encourage connections and social interaction, thereby increasing creativity and innovation—that’s our real value to our clients.

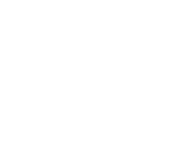

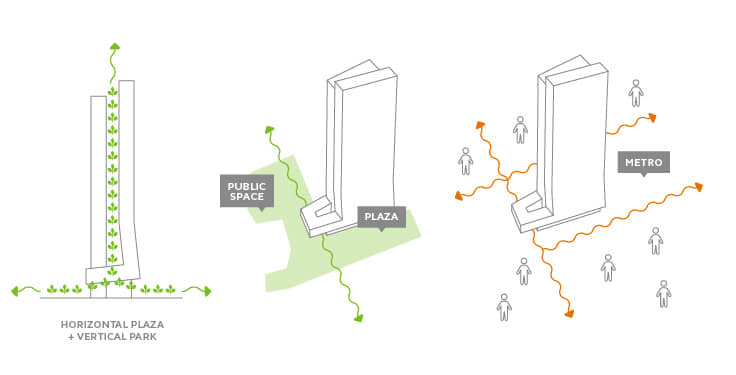

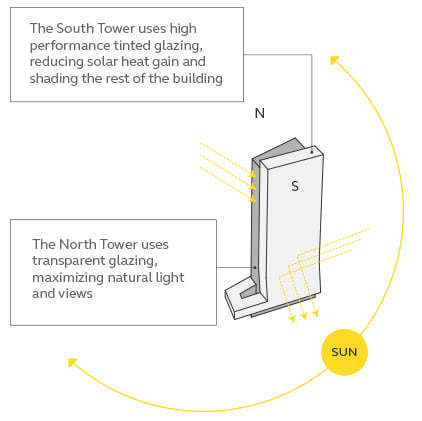

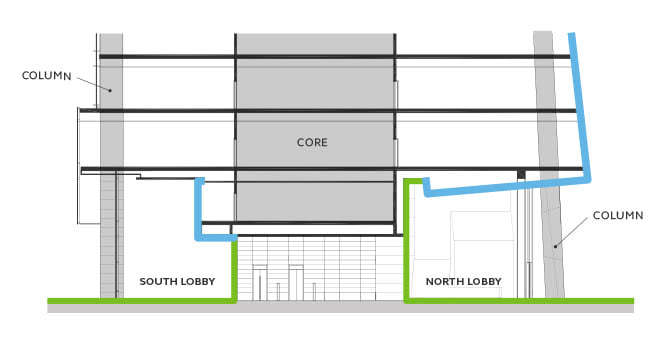

Going back to the area of Shenzhen where I had my lengthy, complicated walk down the street, it had a silver lining—when I designed China Life, I created a place that is the exact opposite of what I experienced. The ground floor can be entered from multiple sides so the building connects with open space around it. There is a public plaza surrounding the base of the building to encourage community connections. The building volume is expressed as two towers, which also represent China Life’s brand. This has the added benefit to the community and city of reducing energy consumption.

Through the elevated podium, the building adds transparency on the ground level, dissolving the boundary between interior and exterior and creating visual and physical connections with the rest of the neighborhood. The sculptural columns at the base not only form an artscape for people to enjoy, but represent the organic, growing strength of Chinese culture and China Life, the largest insurance company in the world. The conference center is a hub for innovation, welcoming international visitors who collaborate. The 36-story tower opened recently, and already we can see how this business district is emerging, how people are using the space differently.

In the urban condition, everyday experiences are interconnected. How you get to work, who you see and how your environment encourages or hinders your interactions with others make a substantial impact on creativity and productivity. And when factors like design, circulation and collaboration are just right, that’s when a city is poised for meaningful, widespread innovation. And even a “pop.”

Photography copyrights © Paul Dingman