Commuting in London: If You Stand Still You Go Backwards

CRTKL’s Lucas London and Maren Striker debate how best to traverse the city of London.

London, with its charming high streets and network of narrow roads connecting town centres, has a ‘village in the city’ atmosphere not found in rivalling world cities. Within this backdrop of quaintness, you come to realize how much more crowded this city has become over the years when you make your way across town.

Today in London, it seems we spend an inordinate amount of time in transit. Clogged roads and crowded trains are a part of daily life for Londoners. Those charming streets often create bottlenecks, making a relatively short drive or bus journey progress at a snail’s pace. The tube gets amazingly packed at peak hour, made even more uncomfortable by the low headroom in older trains. More and more Londoners are avoiding the jams on roads and rail by hopping on their bikes, spurring a bit of a cycling renaissance in the city, or using their trustworthy two feet to make their home-work journey.

So what’s the best way to move around London? This op-ed looks at the transportation preferences of two CallisonRTKL’ers in London, reflecting on the pros and cons of the city’s mobility options and suggesting improvements that could be made to increase safety, usability, comfort and convenience.

London by Bike? No thanks. Where’s the nearest tube station?

Lucas London is a transportation architect/urban designer from the United States working for CallisonRTKL in London. He has been living and working in London since January 2016, using public transportation as the major home-work commute.

It’s another morning at the King’s Cross St. Pancras Tube station platform, and there I am shuffling with a crowd and trying to squeeze onto the train that has just arrived. Peering from the platform into the train, I see people standing about in the centre of the carriage with plenty of personal space and newspapers spread open, seemingly oblivious to the jam of people at the doors just two steps away. People politely ask others to step down in a courteous English way, and the doors close before half of the mob can get in. There goes another two minutes of commuting time (or five on a day with train delays), as I precariously stand at the platform edge waiting for the next train.

This situation is common in all metro systems around the world, and while Tokyo has ‘pushers’ to forcefully squeeze people in, I would have thought that of all places in the world, London would have a proper way to get people to move into the train cars besides pleasant audio reminders and posters.

Nevertheless, I’m sticking with taking the tube because it beats the alternatives. Driving, taking a bus or taxi would be no faster during rush hour as the roads are clogged. Living nine miles from the office is a bit too far for a daily walk, though I do occasionally run part of the way home through greener parts of London—a great way to combine commuting and exercise. And while I applaud the many who have taken to cycling in London, it is just not for me. Sharing narrow and often wet roads that lack space for cyclists with cars and trucks manoeuvring just inches away from me—all while inhaling exhaust—is not my idea of a commute. Health and safety moment anyone?

So while the tube has its woes, it’s still my mode of choice. Once I negotiate the crowds and find a place to stand vertically at the centreline of the carriage (Ok, I’m 6’-3”, but were people really that much shorter when they were building the tube 150 years ago?), I relish the time to read, write (this blog included), daydream or just close my eyes and clear my mind. But there are still ways that the tube and other commuting tools can be improved.

Aside from adding additional rail lines, or even enlarging the tunnels for taller trains (which would be amazing), here are some simpler remedies to improve transport in London:

1. Replace half of the seats in train carriages with perch seating or fold down seats. The big, plush armchair seating feels of a bygone era and takes up too much space. Some of the traditional seats should be retained for riders that legitimately need a seat, but for the masses, perch seating would be a happy medium between density and comfort. Fold down seats, which already exist on some trains in low proportion, would yield more space for standing during peak hours whilst still providing a seat during off-peak hours.

2. On buses: The stops are sometimes way too close—at times as close as 150-200 meters—despite relatively low development densities. This means the bus is stopping quite often instead of making forward progress. Slightly longer distances between stops would help to speed up buses without adding too much walking time/distance to one’s journey. 300 meters between stops is about right.

Beyond the physical transit network, city development and behaviour patterns can be changed to benefit transit and urban lifestyle:

1. Build higher density, mobility-oriented development near stations and within 500 meters of transit. Encourage smaller satellite town centres to become new hubs for live/work/play to distribute traffic away from a single urban centre.

2. Encourage companies to stagger their working hours and create a culture of flexible/remote working to reduce the peak hour demand. This strategy would not only free up space on the tube, but also reduce people’s need to commute, yielding more personal time and new ways for people to interact with their community and their work (ie, local ‘work hubs’ for remote working).

The Tube? No thanks. I’d rather take my bicycle!

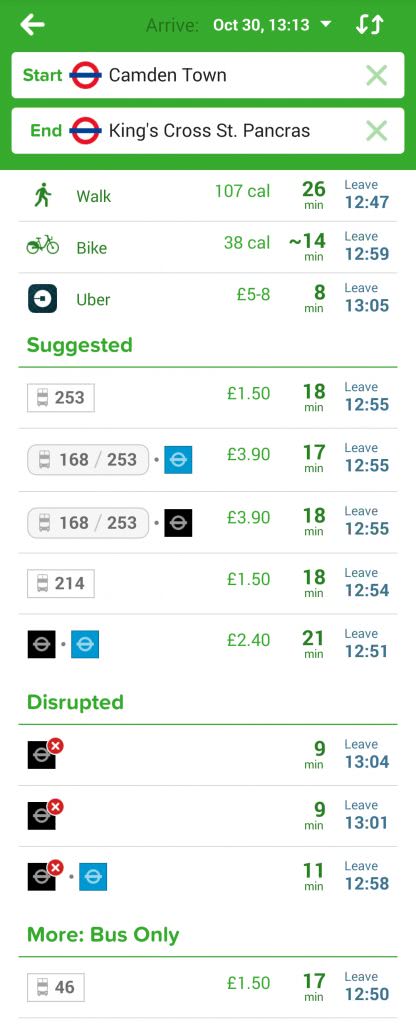

A common theme during the weekends in London: the tube is disrupted; cycling is the quickest and cheapest option while walking is almost competitive with the bus and rail.

Maren Striker is an urban planner from the Netherlands working for CallisonRTKL in Berlin. He was a resident in London for the past 1.5 years and is an active home-work cyclist.

The tube, love it and hate it—at least I do. Certainly, the oldest metro system in the world has its charm. The station design takes you back in time, the voice over in the train is so lovely British and people from all walks of life use the system on a daily basis.

However, noise levels are so high that a normal conversation is not possible on most of the (older) lines, major rail improvement works on weekends result in closures of stations and lines, and heavy overcrowding during rush hours becomes a growing inconvenience. This is all accepted even though a significant amount of your monthly salary (about GBP 130 per month for a monthly pass in zones 1-3) goes straight into a home-work transportation commute.

Obviously, I understand you cannot compare the relatively new metro systems in Singapore or Hong Kong with the world’s oldest. However, as a (former) resident of this city and as a town planner, I refuse to accept that the transportation I pay for is so inconvenient and out-of-date.

I’d rather hop on my bike and discover the hidden streets in Europe’s largest city. London consists of an amazing network of neighbourhood roads that take you swiftly from one place to another.

The following improvements would be beneficial to create a better understanding among traffic users and to ensure a more even modal split among the various transportation options available in London.

1. Compulsory traffic examination at age 11: There is no mutual understanding between car drivers and cyclists in London or the UK in general. I believe that is largely because many drivers (especially cab drivers) never sat on a bicycle and do not understand how vulnerable you are in traffic as a cyclist. On the other hand, many cyclists underestimate the fact that if you are confident and signposting clearly where you want to go, drivers will anticipate. A commonly made mistake among cyclists is that they make sudden movements which results in chaotic and unexpected traffic situations. In the Netherlands, a compulsory traffic examination (theoretical and practical) is taken at the age of 11, increasing awareness on a young age about traffic rules and your role as a cyclist in traffic. Teaching the proper techniques to younger children in London could help alleviate some of these issues.

2. Make a complete network of bicycle paths. The London bicycle plan for infrastructure is adhering to ‘bicycle highways.’ While this is a positive development, part of the reason drivers and cyclists are not happy with each other is that as an unexpected ‘by-product’ of the bicycle highways, ignorance of drivers to cyclists has emerged on all other roads. A holistic infrastructure plan is the solution, giving equal share to cars as well as cyclists, pedestrians and all other forms of transportation—accommodating rather than ignoring the diversity of the road. Where bicycle paths must share the space with higher volume roads, keep adding separated bike lanes. Also, giving priority to cyclists over motorists, particularly on right turns is a good step in the right direction to create a safe and shared road network. Good examples can be found globally, from Amsterdam to Bogota, Copenhagen to Beijing, where the road is shared among multiple users and functions.

3. Road improvement. I have cycled in many of the world’s largest metropolises including Shanghai, Beijing, Bangkok and Jakarta, to name a few. I have never seen such poor quality of asphalt in any of those cities as I have in London. Too often the asphalt and speed-bumps in London make it feel I am on a mountain bike trip: up the pavement, down the pavement, no hard shoulder, braking tracks from busses that make me divert from my cycle lane. The city should make simple improvements that will ease the frustration between drivers and cyclists. With the current road quality, no wonder cyclists start to feel unsafe, and no wonder drivers are frustrated by the sudden movements of cyclists.The above simple measures will result in more people using their bikes, a safer and cleaner environment and a reliable and complementary commute option.

Closing Thoughts

All in all, London does a good job managing its transportation network, coordinating its 150-year-old tube system with an even older network of national rail lines and organizing buses, ferries, a tram, an aerial cable car, motorbikes, scooters, cyclists, skate-boarders and pedestrians. However, if you stand still you go backwards and continuous improvements are necessary to keep accommodating to the changing behaviour of citizens.

It is essential for government and transportation agencies to recognize that modal choice is a personal decision and that there is no silver bullet to solving a city’s transportation. Despite opportunities to improve each mode, the strength of London’s transit system is that it offers options to suit different people with unique transportation needs and preferences. Every world class city should offer transportation options that complement, not compete, with one another. In a world where many cities are struggling to offer at least one viable alternative to driving, the answer just may be to invest over time in more than one option and to be prepared to constantly renew and improve transit incrementally over time.

You are so right!

Also Berlin has room for improvment in public transportatiion and cycling.

I like the idea of the traffic examination at age 11.

You are BOTH right! Choice of mode should be our objective;) Diane

Interesting article from the perspective of a real user instead of “Designer”.