DC Affordable Living Competition: Energy and Water

This is the second in our series of posts about the 2015 DC Affordable Living Design Competition. CallisonRTKL is working on a design for 10-15 single-family affordable townhomes in the Deanwood neighborhood of northeast DC that meets the mandates of the Living Building Challenge (LBC), widely recognized as the world’s most ambitious building performance standard. The LBC uses the metaphor of a flower deeply rooted in its place to give shape to its holistic design criteria. It is structured around seven performance categories, or “petals,” representing aspects of sustainable design: Place, Water, Energy, Health and Happiness, Materials, Equity and Beauty. This blog addresses the Water and Energy petals.

The water and energy petals are simultaneously two of the simplest and most challenging petals of the Living Building Challenge. The mission is simple: net-zero water and net-positive energy. The execution? Well, that’s a bit more complicated.

Energy

You’ve probably heard of Net Zero Energy: the concept of a building or process consuming equal or less energy on an annual basis than it produces renewably. The Living Building Challenge, as always, takes this already challenging task and sets an even higher target. In Version 3, the Living Building Challenge requires that their buildings reach Net POSITIVE Energy, meaning that they produce at least 5% more energy than they consume on an annual basis.

It’s a slight but important distinction. Is it really enough that sustainable buildings simply come out even? Or should they become the vehicle for generating a more sustainable society, one that is markedly better than the past?

This, in a nutshell, is why the Living Building Challenge is such a leader in the field—because it is always questioning and pushing the envelope of defining what makes a building truly sustainable.

So what does all of this mean to Deanwood and to our project site? In order to design to the Living Building Challenge standards, we will have to reduce energy demand as much as possible and supplement that demand with on-site renewables such as photovoltaics or solar thermal collectors. For this, design plays a very important role.

Passive design decisions made at the beginning of the design process—such as site planning, solar orientation and control, daylighting and natural ventilation—can have the most impact on reducing the demand for the building to be heated, cooled, ventilated and lit using electricity. But as the building design becomes more efficient, how the occupants operate the space wields an even larger influence on overall energy usage.

A recently completed student housing project at the University of California at Davis learned this lesson the hard way. Since opening in 2011, the project has been unable to reach Net Zero Energy. Its main setback? The students. The students have used more electricity to plug in electronics and more hot water than predicted, and the designed photovoltaic system cannot generate enough energy to make up for the plug loads and heating.

This drives an important point home. It takes more than just one designer to create a Net Zero or Net Positive Energy project. It takes a community of passionate and knowledgeable people who are willing to work together to create a sustainable world. Thankfully, if there is any neighborhood in DC passionate enough to work together toward this common goal, it is Deanwood.

Water

At the first charrette, one of the presenters offhandedly quipped that while it is possible to achieve net-positive energy, there really is no such thing as net-positive water. This statement struck a chord because not only is this true at our site’s scale, it’s true for our entire planet. The amount of water we have doesn’t change. More than enough solar radiation falls on the earth every hour and a half to power the world’s annual electricity consumption with only solar power, but the amount of fresh water on the planet is finite and limited.

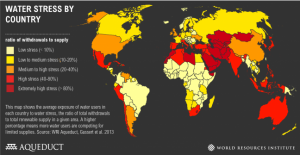

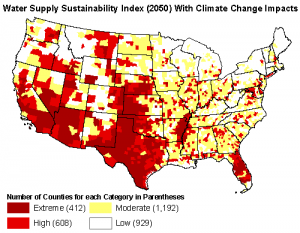

While achieving net zero water for a housing project in this climate will be challenging, it is a critical issue to address at a global and local scale. For several years, authors and scientists have been hypothesizing that the next large wars could be over water, as it is an increasingly scarce resource in many parts of the world. Access to clean water continues to be an issue for much of the global population. We see evidence of this today with extreme droughts in California and other parts of the world, as well as catastrophic events such as tsunamis and floods that limit access to clean water. Simultaneously, the demand for manicured lawns and lush landscapes in desert climates continues to rise as developing nations seek to flaunt signs of modernity.

With 768 million people worldwide lacking access to an improved source of water, 2.5 billion people without access to improved sanitation, and global water demand projected to increase by an estimated 55% by 2050, we need to consider every drop of water a valuable resource. For our site, we will need to capture all rainwater for indoor and irrigation reuse, treat all wastewater on-site for reuse, and celebrate the use of water through productive landscape features such as vegetable and fruit gardens.

Images: Davide Restivo, The Living Building Challenge v3.0 overview, World Resources Institute, Natural Resources Defense Council