Megacities and Polycentric Planning

“Louvre reopens after heavy flooding shuttered Paris museum.”

“Mexico City orders all cars off the road one day a week to tackle air pollution.”

“Beijing takes lead from London, Singapore as it plans congestion charges to curb capital’s huge traffic jams.”

A look at the day’s top headlines is profoundly telling in terms of the challenges our cities encounter in the face of a changing climate, diminishing air quality, environmental degradation and population increase. An added sense of urgency is in part due to the rise of the megacity. The number of megacities—each with a population of 10 million or more—has risen from two in 1950 to 35 today, with the number projected to reach 40 by the year 2030.

Historically, cities have maintained an atmosphere of intense competition, but moving forward, we cannot afford such an inward-looking approach. Why? In short: capacity. Isolation and tension result in missed opportunities of considerable magnitude for synergy and cooperation. As cities continue to grow and resources dwindle, it is imperative that we maximize connectivity.

Given that future cities are dependent on high-density, mixed-use development, we look to two very different countries where CallisonRTKL and our parent company, Arcadis, have a significant presence: the Netherlands and China. As the latter grapples with unprecedented population growth and attempts to define responsible, sustainable urban development, the former can teach relevant lessons about how a model of urban design known as polycentric planning can be revived and tweaked to overcome modern-day obstacles.

How the Dutch Developed

Urban development in the Netherlands has been polycentric in nature since the 14th century when the need to build a network of dams and terps (artificial hills) for flood protection marked the start of spatial planning. For centuries, the cities acted as powerful figureheads for the region: well-connected to the surrounding towns and villages, but also autarkic—so much so that, even to this day, each city maintains its own strong culture and profile.

In the 1960s, the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) issued data predicting that the Dutch population would double by the year 2000. The government responded with a compact urbanization policy known as concentrated de-concentration. Large cities were deemed undesirable, and open space was prioritized for the sake of health and wellbeing.

The policy met with criticism in the 1980s as people increasingly saw a need for Dutch cities to connect their strengths in order to complete in the global economy—the “borrowed size” or agglomeration benefit approach. At this point, polycentrism was officially born, with each of the major cities acting as part of a conglomerate with the goal of offering a high standard of living. Three decades later, this has materialized into a society where commutes are short, work-life balance is a priority, eco-systems are maintained, development is designed and planned for the human scale, and infrastructure and offerings are world-class.

China: A Critical Testing Ground

The urban development story in China begins later than that of the Netherlands and unfolds much more quickly and haphazardly. According to The World Bank, 260 million migrants have moved to China’s cities from rural areas over the last three decades, placing unprecedented strain on the country. Home to the world’s largest emerging markets and nine of its megacities, China’s evolution from a manufacturing and investment-led economy to a consumer-based economy has spurred unparalleled growth. New development has sprung up seemingly overnight in alignment with the interests of local government and opportunistic developers.

Yet it is also here that evidence of the planet’s most perilous challenges is present in the air pollution masks worn by Chinese citizens, and quality of life is threatened by crowded conditions and high property prices. Furthermore, the megacities are just one tier of a multidimensional country. Second- and third-tier cities clamor for first-tier status, while the fourth-tier struggles to provide basic infrastructure and an acceptable standard of living. Meanwhile, each city has maintained a largely singular focus on its own needs and aspirations without regard for regional or national connectivity. This sets up a challenging dynamic, to say the least.

Polycentrism’s Essential Components

Tailoring a polycentric model to address China’s intensifying urban development relies on a set of parameters informed by two things: structure, which is inherently tied to the city’s past and the evolution of its urban core over centuries, and scale, determined by an honest assessment of present circumstances and future aspirations in a manner that guards against sprawl and sets reasonable growth boundaries.

Identity

Every city benefits from an urban center—not necessarily in the guise of a tower or other architecturally dominant focal point, but a mix of uses with a collectively outsized impact. Universities, medical centers, financial hubs and innovation districts make for excellent urban centers, and when successfully integrated with residential, retail, office and/or hospitality components, each helps to shape a livable, desirable community and becomes the core of its identity. Creative and artistic professionals play a vital role, too; people like Jaap van Zweden, the conductor of the Hong Kong symphony orchestra, and Rem Koolhaas, architect of the CCTV Tower in Beijing, make notable contributions to the city’s evolving culture and often achieve celebrity status that endows the city with a certain credibility and draw. Effective actualization and clever marketing is what attracts businesses, visitors and residents who will help the city thrive.

Every city benefits from an urban center—not necessarily in the guise of a tower or other architecturally dominant focal point, but a mix of uses with a collectively outsized impact. Universities, medical centers, financial hubs and innovation districts make for excellent urban centers, and when successfully integrated with residential, retail, office and/or hospitality components, each helps to shape a livable, desirable community and becomes the core of its identity. Creative and artistic professionals play a vital role, too; people like Jaap van Zweden, the conductor of the Hong Kong symphony orchestra, and Rem Koolhaas, architect of the CCTV Tower in Beijing, make notable contributions to the city’s evolving culture and often achieve celebrity status that endows the city with a certain credibility and draw. Effective actualization and clever marketing is what attracts businesses, visitors and residents who will help the city thrive.

Source: Wyndham Amsterdam

Human Scale and Quality of Life

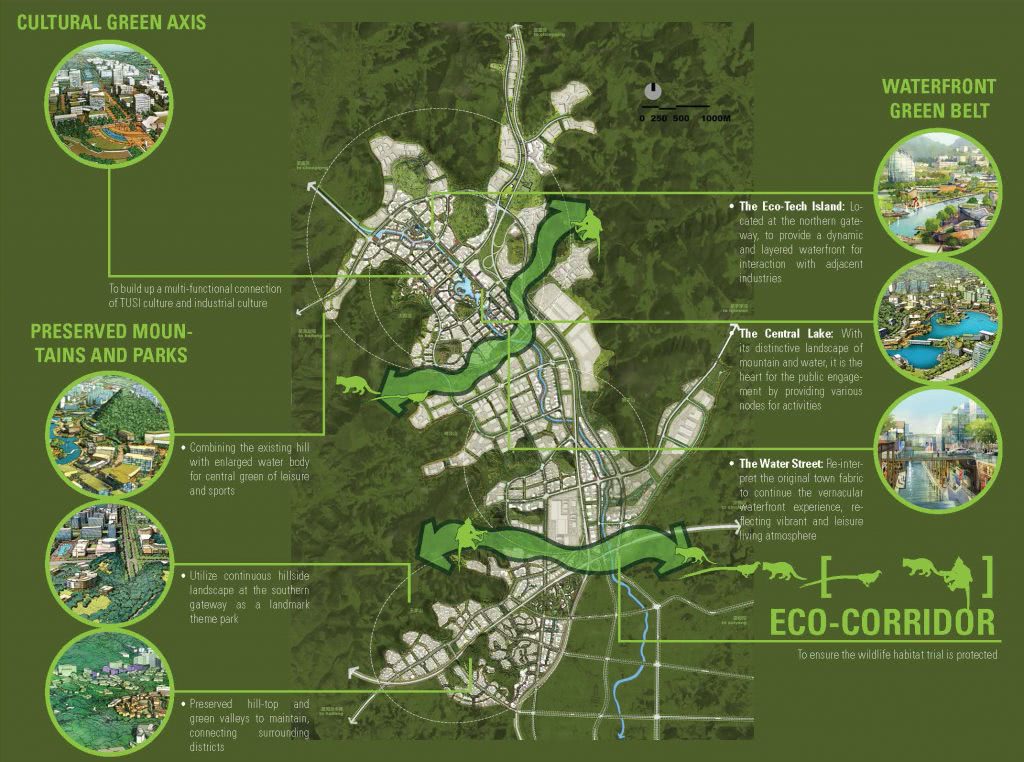

Urban planning on a human scale must take contextual relevance into account, particularly in the evolution from city to megacity. Density achieved on a human scale is further enhanced by cultural offerings, which drive interaction and a spirit of exploration. The spaces where these take place are all the more impactful when green space is woven throughout; besides serving as excellent connective tissue, it heightens quality of life, provides recreational corridors and generates resources for agriculture and water filtration.

Connectivity and Mobility

Finding safe, accessible ways to allow people and information to flow reinforces the positive benefits of polycentrism and is essential as our urban areas are increasingly connected. This applies to aviation and ports, too, which elevate connectivity beyond a regional platform to an international one and raise the city’s global profile. Meanwhile, hubs and stations with a mix of uses tailored to the local market become destinations and economic drivers in their own right.

Knowledge and Innovation

Playing a role in the global network of connected and “smart” cities requires winning the hearts and minds of the talented, entrepreneurial set, who are, more often than not, drawn to cosmopolitan areas. Demonstrating that a city’s educational offerings are engaged in mutually beneficial partnerships with local industry and on the forefront of technology and innovation is not only invaluable marketing; it is essential to a robust and sustainable economy.

Design and Planning

Monocentric planning models have resulted in wealthy cores surrounded by poverty-stricken areas and lower quality of life. While competition draws wealth from surrounding areas, cooperation raises the standards for the region overall. China’s cities and megacities must break out of the monocentric mold and reestablish connectivity if they are to become viable models of urban development and achieve smart density. In the megacity, this will likely mean new strategies for vertical integration and innovative technology, making density more palatable for the end user.

The Virtues of Polycentric Planning

Global powerhouses that act as business, commercial and financial engines for surrounding areas are better positioned to draw upon and distribute resources across a wider network strengthened by connectivity. In China, the construction of a high-speed rail network has made a start by making cities that used to be distant neighbors reachable within 45 minutes. In the Netherlands, this has been applied to great effect, and within these large metropolises, we see multiple “heartbeats”—city centers with their own distinctive economies, competitive advantages and educated working force. This model of urban planning, rooted in a rational and scalable approach, will contribute to healthier, more sustainable cities and megacities.

With contributions from:

Carolien Gehrels, City Executive, Amsterdam and Rotterdam, Arcadis

Maren Striker, Global Development Lead, Buildings, Arcadis