Optimized Mobility and Safer Streets: Creating Harmony Between Transit Modes

At the recent 2017 APA National Planning Conference in New York City, CallisonRTKL released Urban Shift, a compilation of trends and influencers driving the design and development of modern cities along with key project examples. This post is the third in a series that takes Urban Shift a step further in exploring how urban planners can address the environmental, economic and social shifts taking place around the world.

My commute to work is a nearly 40 mile-round-trip through the mean streets of LA, much to the wonder, bewilderment and concern of some friends, family and colleagues. Although being a bike commuter in LA is admittedly not easy, I’m still surprised that more people don’t do it, particularly given our health-obsessed local culture. Biking makes for great aerobic exercise; the climate encourages it and the landscape is relatively flat.

However, while streets take up more than 18% of LA’s land area, there are surprisingly few that accommodate bikes at all, forcing cyclists to brave fast-moving traffic along just a handful of major routes. One of these routes is Venice Boulevard, a major artery that takes people from the beach to downtown. Coordinated signals mean the street largely functions to maximize the flow of automobile traffic.

However, while streets take up more than 18% of LA’s land area, there are surprisingly few that accommodate bikes at all, forcing cyclists to brave fast-moving traffic along just a handful of major routes. One of these routes is Venice Boulevard, a major artery that takes people from the beach to downtown. Coordinated signals mean the street largely functions to maximize the flow of automobile traffic.

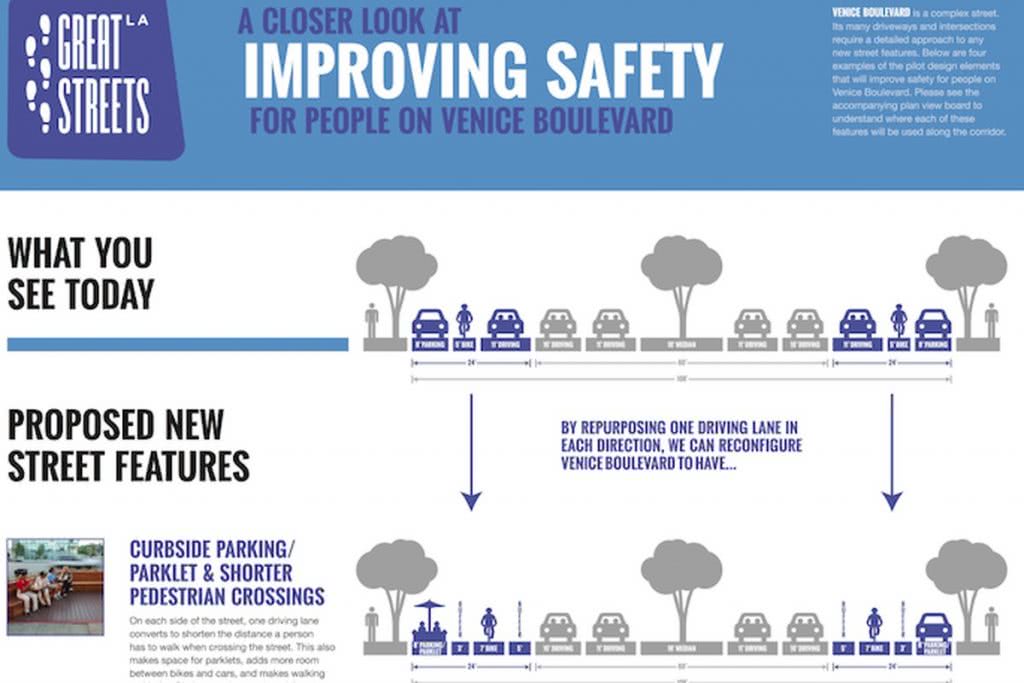

So, while it’s possible to ride a bike along Venice Boulevard, it’s certainly not what I would call a great street for cycling. Its configuration—three travel lanes for cars, a five- to six-foot wide bike lane and on-street parking along the curb—is dangerous for several reasons. When you optimize traffic flow for vehicles, you inevitably embolden drivers to take up higher speeds, exposing cyclists to greater risk. If that weren’t bad enough, parked cars frequently open their doors into the cycling lane; a skilled cyclist can swerve gracefully and quickly enough to avoid a collision, but often, cyclists get “doored,” flying over the car and incurring injuries.

The “complete street” movement (where a variety of transit modes are accommodated in the same right-of-way) was supposed to be the cure-all. But it’s not always well-executed: reducing the width of vehicular lanes to squeeze in a bike lane—a half-hearted attempt at accommodating cyclists at best—creates as many problems as it solves. Since bike lanes have been integrated into LA streets, traffic-related accidents have become the leading cause of death in the city. At 200 deaths annually—nearly half of which are either pedestrians or cyclists—this puts the risk of using our roads in 2017 at a higher level than the risk of being a victim of gun violence. Venice Boulevard has a higher rate of injury than streets of comparable size in LA, and a city survey found that almost 20% of drivers regularly exceed the 40-mph speed limit.

REEVALUATING AND RECALIBRATING

City Council has begun to recognize the importance of this issue and its impact on quality of life. Championed by Mayor Eric Garcetti and funded by a sales tax increase that supports local transit, a plan called Vision Zero brings together traffic engineers, police, advocates and policymakers to eliminate all traffic deaths by 2025. City Council recently approved a $27 million allocation to Vision Zero projects, and as Councilmember Mike Bonin said, “Budgets are statements about our priorities, and I know of no higher priority than saving lives on our streets.”

Along Venice Boulevard, Vision Zero has identified a nearly mile-long stretch from Inglewood Boulevard to Beethoven Street in the Mar Vista district of west LA. Vision Zero will take note of best practices for cyclist and pedestrian safety across the country, particularly the Great Streets initiative in New York City, and will also look to create an environment that is friendlier to the human scale: during outreach events, locals expressed a desire for a “small town, downtown feel.”

Image via Councilmember Mike Bonin

A few key strategies are making a tremendous difference in making our streets safer and creating harmony between different transit modes:

Crosswalks

Increasing the number and visibility of crosswalks and shortening the distance that pedestrians must cross have proven to be effective. To that end, four new crosswalks with high-impact patterning have been installed along Venice Boulevard.

Head starts

Pedestrians receive a walk signal a few seconds before drivers get a green light, giving them another small advantage as they stake their claim on street space before overly zealous drivers cut them off.

Protected bike lanes

More robust protection is being implemented in the form of physical barriers between cyclists and moving traffic along with parking lanes and painted buffers with bollards that accommodate space for opening car doors, protected seating and standing areas for food trucks and loading/unloading.

TRANSIT TRADE-OFFS

Predictably, there has been some pushback: a group called Residents Against Cut-Thru Traffic formed to voice collective concerns about the impact of reducing the number of travel lanes from three to two, arguing that it may divert commuter traffic to residential streets. This is a logical concern, but in a city notorious for traffic problems, where pedestrian and cyclist collisions with cars are a regular occurrence and where the quality of life of all Angelinos is negatively impacted by traffic, it’s essential that we prioritize progressive mobility solutions.

If the city is to evolve, the way we get around must accommodate a wider variety of transit modes. It’s not just about safety; it’s about optimizing mobility and reflecting the diversity of our citizenry and how they choose to get around.